The Nobel Prize: it’s a Changin’

November 17, 2016

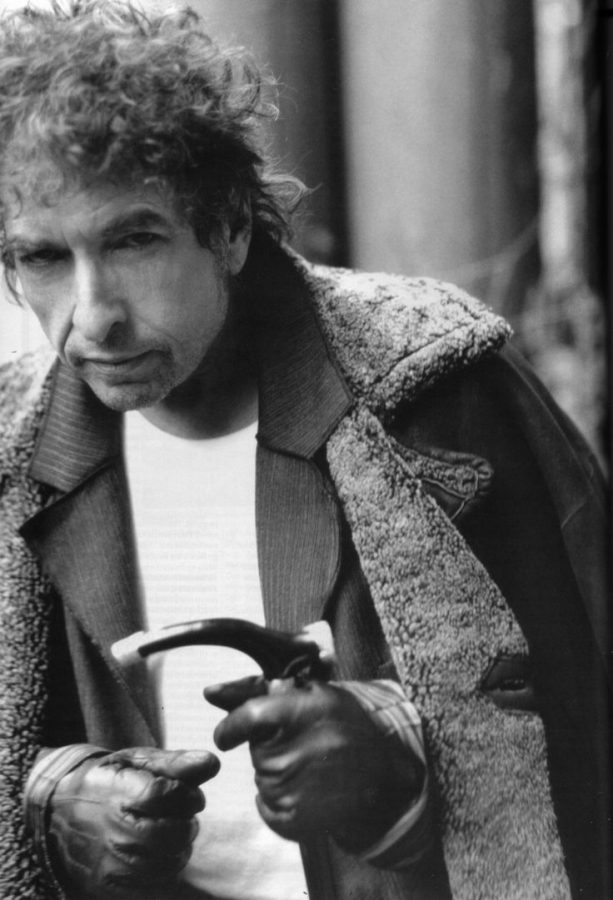

On October 13th, Bob Dylan became the first musician ever to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Not everyone is pleased to see the rebellious folk hero slouching next to the likes of Hemingway, T.S. Eliot, Steinbeck, and Solzhenitsyn. Of these awards given annually to a writer whose work is deemed “in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction,” controversies have been anything but unusual. Winston Churchill received the award in 1953 for his work in autobiographical work and oratory – styles which many do not consider to have intrinsic literary merit. Moreover, in 1964 Jean-Paul Sartre refused the award to not show particular preference for Western culture during the Cold-War era, although with the passage of a few unfruitful years Sartre would petition in vain for his unclaimed prize money.

At its heart the controversy is about what people in the world today, not just the Swedish Nobel Prize Committee, wish to honor as meaningful writing in the canon of human creation. Literature is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as written works, especially those considered of superior or lasting artistic merit. The joys of music and writing have always been intertwined, and as the secretary of the Swedish Academy said, “the work of Homer and Sappho was not only meant to be read aloud, it was often accompanied by music.” Many people today would say their most frequent encounter with writing (specifically that which they regard to be profound and impactful) is through poetry in musical compositions. Certainly there is an irreplaceable experience to be cherished in good books or collections of poetry, but the question of whether professors and critics are willing to acknowledge the most commonplace medium of literature today warrants serious attention.

Regardless of one’s individual perception of what merits a literary work, many argue that the flaw in this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature is the Laureate himself. Many of Dylan’s critics assert that there are other musicians whose lyrics are better crafted, make bolder statements, but remain deprived of sufficient acknowledgment due to the influence of already well-known artists like Dylan. Yet, in the past, many Laureates have been lesser known writers who have emerged from the cracks because their statements have been more powerful than those who already have the sway of fame. Others refute that, while countless rhetorically talented artists, authors, and musicians deserve more recognition for their work, there are a few like Dylan, who have gained their popularity because their words possess so much meaning. This year Dylan’s supporters say that the prize goes to someone whose voice has resonated in the lives of many for years, and whose poetic diction and strong political implications deserve to be recognized in full.

Many find that the trouble with the 2016 Nobel lies in the maintenance of tradition. For such a momentous and time-honored award, it is crucial that past mores are maintained and music remain distinct from literature. According to Anna North of the New York Times, despite his skillful lyrics, published work of prose and poetry, and popular autobiography, “Mr. Dylan’s writing is inseparable from his music”. However, others believe Dylan’s lyricism makes him all the worthier of receiving the prize, as it demonstrates that music and literature can be inseparable– it is the message and structure of the work that should be judged. “I like it. Literature is large.” says Teju Cole, author of the novel Known and Strange Things. Certainly, the definition of literature is being greatly challenged, and peculation continues in terms of whether this shift should be welcomed or shunned.

Following the announcement of Bob Dylan’s Nobel prize, the “voice of a generation” stayed notably mute on the issue. After a manager updated his website to mention the prize in a single sentence, Dylan had this taken down as well. Conjectures abounded, labeling Dylan as anything from a conceded rock star who never lost his attitude, to a folksy purist, whom Don Mclean called “a voice from you and me” in the song American Pie, and who surely wouldn’t humor an elitist rabble of critics by thanking them for their conclusion. Some even proposed that Dylan, known for haranguing militarists with acrid words such as “you who build the big bombs, you who build the death planes” … “I hope that you die, and your death will come soon” (from Masters of War), would never condone the award created by Alfred Nobel – the man responsible for the invention of dynamite and every explosive thereby inspired. One could easily forget the Nobel Prize in Literature in awarded not only for “outstanding work”, but also that which is “in an ideal direction” and exemplifies the potential that the human race struggles to become. This quality is immediately manifest through Dylan’s extensive engagements with themes of peace and civil rights, but therein arises the question of whether the artist must actually backtrack against his own distaste towards military industry by acknowledging an award in memory of Alfred Nobel.

Nearly three weeks after the announcement, Dylan quieted a disgruntled Nobel Committee and apprehensive public by accepting the award – although the Committee maintains he would have been recorded as this year’s winner regardless. “Isn’t that something?” Dylan said of having won. 75-year-old Dylan told the Telegraph he would “absolutely” attend the award ceremony this December “if it’s at all possible.” When pressed about the meaning of lyrics that may have resulted in his winning the honor, Dylan merely said “I’ll let other people decide what they are. The academics, they ought to know. I’m not really qualified. I don’t have any opinion.” Thus the freewheelin’ artist preserves his legacy of straddling the line between visionary lyricist – one who changed his name to that poet of Dylan Thomas – or “more of a song and dance man” as he described himself in 1965 when pressed about whether he was a writer or a musician. Apart from how Dylan has felt or chooses to publicly portray himself, the Swedish Academy has boldly shown support for the profound literary work that Dylan gave us all.